Introduction: The Monster Beneath the Waves

Long before dinosaurs thundered across the land, before birds first touched the sky or mammals took their breath, Earth’s oceans belonged to something else entirely—something older, armoured, and monstrously alien. Meet the ancient sea scorpion, a real-life nightmare that once dominated the prehistoric seas with serrated claws and a sinister silence. These creatures weren’t myth—they were monsters of the Paleozoic deep, and some stretched over two metres long, making today’s predators look positively polite.

If you’ve ever stared at a fossil and felt that quiet hum of time beneath your feet, you’ve brushed against the shadow of a Eurypterid—the ancient sea scorpion’s scientific name. With jointed legs, clawed pincers, and exoskeletons that glinted beneath ancient sunlit tides, these prehistoric sea creatures were a strange fusion of arthropod elegance and evolutionary menace. For a time, they were Earth’s apex predators, roaming oceans, rivers, and perhaps even the shoreline, long before vertebrates dared to rise.

But why should that matter now? Because the story of the ancient sea scorpion isn’t just buried in stone—it’s etched into the blueprint of everything that crawled, swam, and survived after. These oceanic beasts hold the key to understanding evolution, extinction, and the very origin of monsters in both science and myth. They remind us that the sea has always hidden secrets—and some are far older, and far stranger, than we ever imagined.

What Is an Ancient Sea Scorpion?

Imagine a creature that looked like a cross between a modern scorpion, a horseshoe crab, and something out of a forgotten deep-sea myth. That’s the ancient sea scorpion—a member of the now-extinct Eurypterid family, and one of the oldest known marine predators to ever crawl through Earth’s waters. First appearing around 470 million years ago, these eerie arthropods ruled long before dinosaurs even blinked into existence.

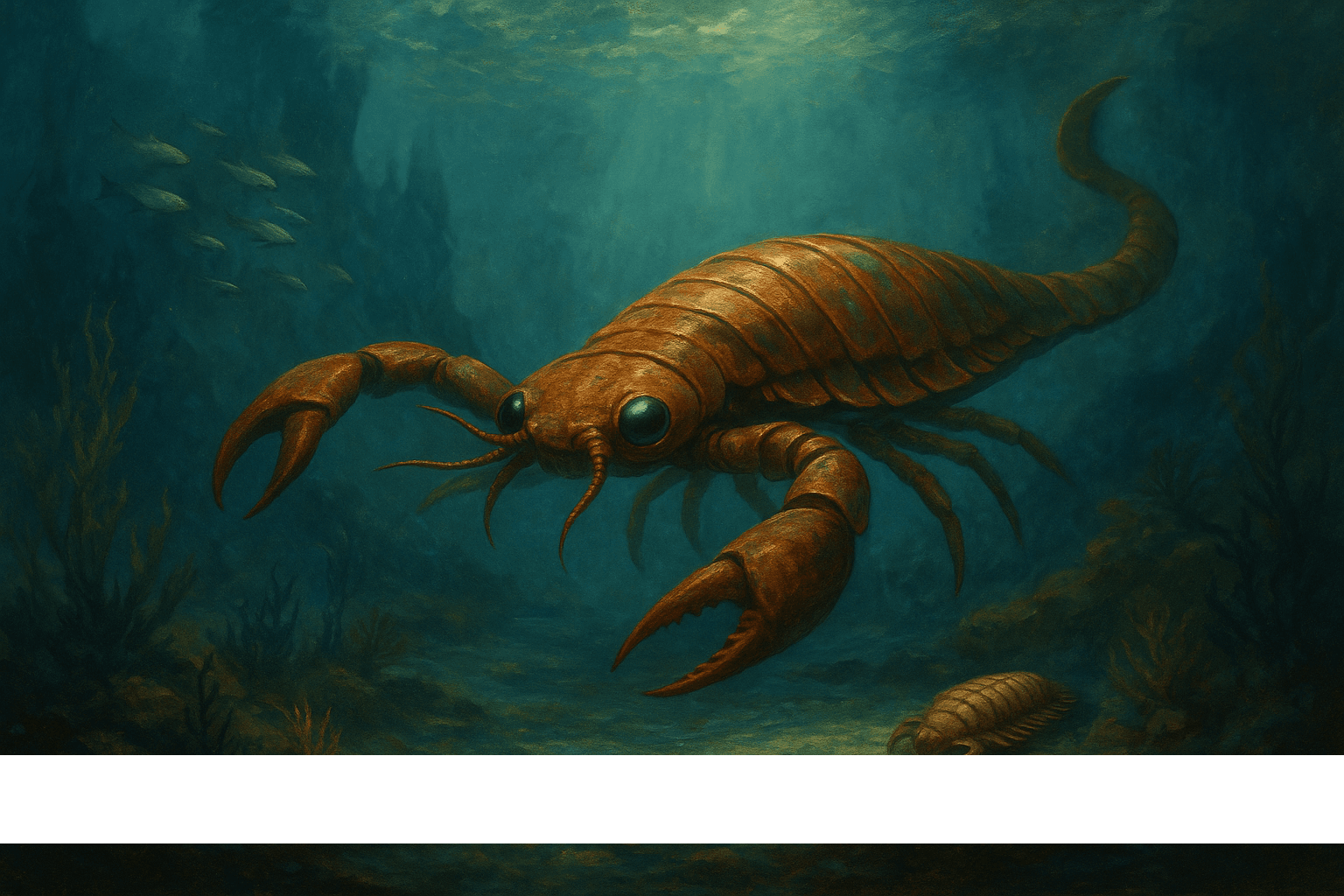

Despite the name, ancient sea scorpions weren’t true scorpions. They were distant cousins—part of the arthropod family tree that also includes spiders, crabs, and insects. What set them apart was their size, structure, and lifestyle. Some species, like Jaekelopterus, grew over 2.5 metres long, wielding huge clawed appendages that could grasp, slash, or pin down prey. They had paddle-like limbs for swimming and a segmented, armoured body that gave them an almost alien grace—if aliens wore plated battle suits and prowled riverbeds.

But it wasn’t just their size that made them terrifying. These prehistoric sea creatures were built for dominance. Their anatomy speaks of a creature evolved for ambush, adapted to murky waters where survival meant being silent, swift, and strong. Fossil records suggest some species could even leave the water for short stretches—dragging themselves across tidal flats, maybe hunting along the shoreline, or evading bigger threats as life on Earth evolved around them.

You’ll find their remains scattered across ancient seabeds now turned to stone—Scotland, Germany, New York, and Estonia all holding fragments of their fossilised legacy. These relics are more than just bones and exoskeletons; they’re echoes of a time when the ocean didn’t just hold life—it dictated it. Each fossil unearthed peels back the curtain on a forgotten chapter of our planet’s story, written not in ink, but in ancient sediment and silent teeth.

When and Where Did Ancient Sea Scorpions Live?

To understand the true reign of the ancient sea scorpion, we have to travel back—way back—into the Paleozoic Era, a time before plants had fully claimed the land and when Earth’s atmosphere was still learning to breathe. These prehistoric predators first emerged during the Ordovician period, roughly 470 million years ago, and thrived until their extinction near the end of the Permian, some 250 million years ago. That’s over 200 million years of evolutionary dominance—outliving many of the creatures that came after them.

During their prime, sea scorpions prowled a very different world. The continents weren’t where we know them today; landmasses were scattered and drifting, with vast, shallow seas covering much of the Earth’s surface. These briny habitats were the perfect hunting grounds for Eurypterids, who likely thrived in both saltwater and freshwater environments. Some species may have stuck to murky estuaries and inland lakes, while others dominated coastal marine zones, swimming through reef-filled shallows and ancient deltas like silent predators in liquid armour.

Fossil hunters and palaeontologists have uncovered sea scorpion fossils across the globe, revealing how widespread and adaptable these creatures were. Scotland is home to some of the oldest and best-preserved specimens, pulled from the Silurian-aged rocks of the Pentland Hills. In New York State, ancient sediment layers reveal impressions of claw marks and paddle strokes—like time’s fingerprints etched in stone. Other rich fossil beds have been found in Germany, Estonia, and parts of Canada, each one adding new clues to the sea scorpion’s complex evolutionary journey.

These fossils don’t just tell us where ancient sea scorpions lived—they hint at how they moved, what they hunted, and how their world changed around them. From shallow seafloors to murky riverbeds, their trail stretches across forgotten continents and vanished oceans, mapping a life form that was both adaptable and deeply entwined with Earth’s early aquatic ecosystems.

The Anatomy of a Prehistoric Predator

To truly appreciate the power and presence of the ancient sea scorpion, you need to look past the fossil and into the form. This wasn’t just a big bug with claws—this was a purpose-built predator, shaped by millions of years of primal competition beneath prehistoric tides. Its anatomy reads like nature’s blueprint for intimidation: efficient, versatile, and terrifyingly elegant.

At first glance, the Eurypterid body resembles something between a scorpion and a submarine. A long, segmented torso was capped by a broad head shield, or carapace, with eyes placed high for maximum visual coverage. This panoramic vision likely helped them track prey and avoid larger threats in the murky, ever-shifting waters of Earth’s ancient oceans and rivers.

But it’s the pincers, or chelicerae, that get the most attention—and rightly so. These clawed appendages came in various sizes and shapes depending on the species, but many were adapted for seizing, gripping, and slicing through soft-bodied prey. In larger species like Jaekelopterus, the claws were powerful enough to crush or impale smaller creatures outright, functioning like nature’s grappling hooks—no mercy, no escape.

The ancient sea scorpion’s mobility was just as refined. It had jointed limbs for crawling along seabeds, and specialised swimming paddles—flattened rear appendages that acted like oars. These made it not just a crawler, but a surprisingly agile swimmer, capable of sudden bursts of speed to ambush prey. Some researchers believe these predators could even glide or swerve through the water with a degree of grace, making them as elegant as they were deadly.

Its exoskeleton was no less impressive—a tough, chitinous armour that offered protection from rivals and predators alike. This natural plating, often ridged and patterned, fossilised exceptionally well, which is why we know so much about their structure today. In some specimens, even the tiny sensory hairs and segmentation details have survived, whispering clues about how they sensed movement, pressure, and vibration through the water.

And while many people imagine these creatures lurking only in the depths, evidence suggests that at least some species were amphibious, capable of hauling themselves onto land for brief periods. Whether to mate, moult, or escape aquatic threats, it adds yet another layer of complexity to an already formidable animal—one not just bound to the sea, but bold enough to touch the shore.

Ancient Sea Scorpion vs. Other Prehistoric Predators

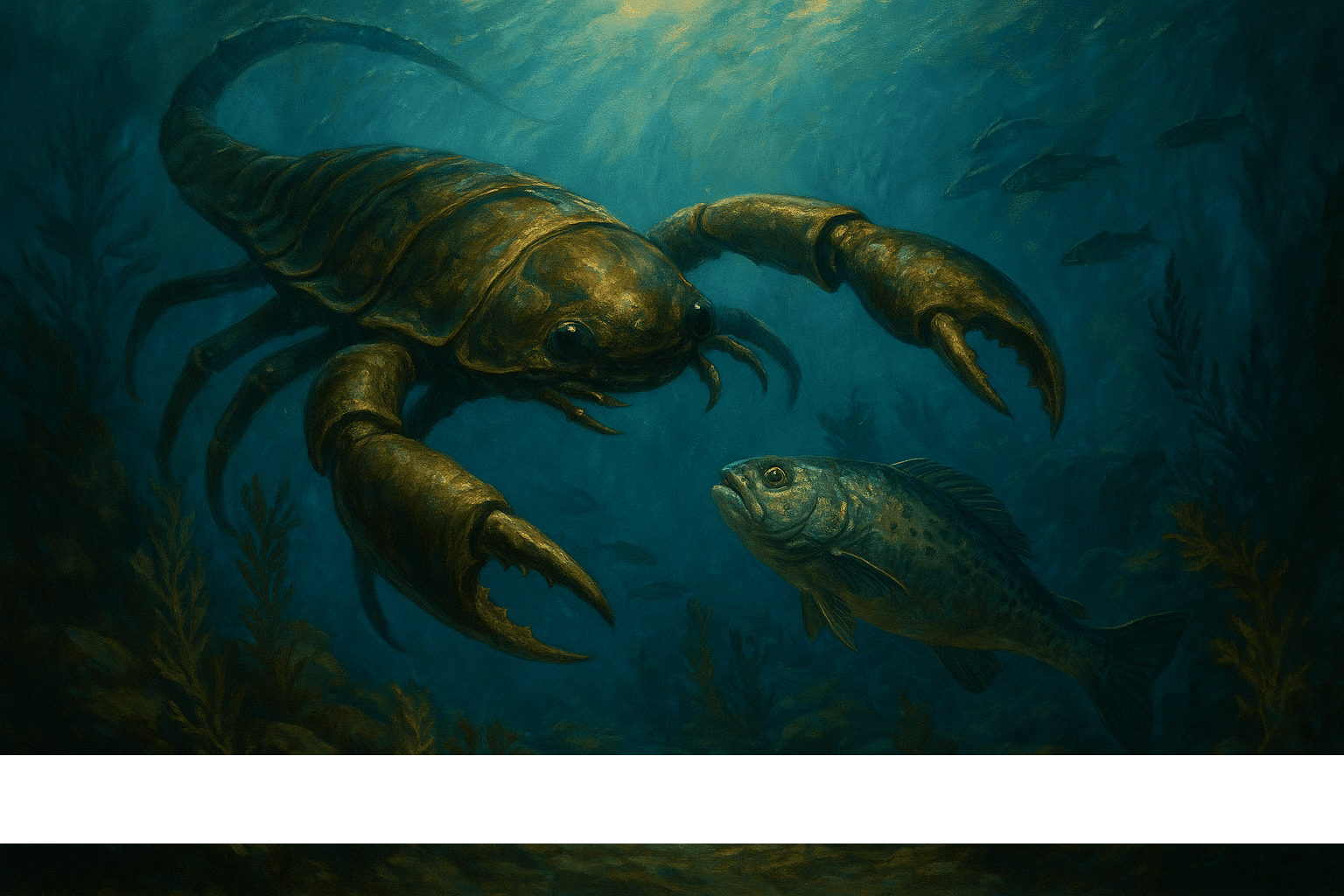

When we talk about prehistoric predators, most minds leap straight to the thunder of T. rex or the jaws of Megalodon—but long before those titans ruled land or sea, the ancient sea scorpion had already carved out its legacy as one of Earth’s earliest apex hunters. In the hostile oceans of the Paleozoic Era, being first often meant being fiercest, and the Eurypterid earned its fearsome reputation through both design and dominance.

Unlike many predators of its time, the sea scorpion wasn’t built for brute force alone. While Anomalocaris—a Cambrian oddity with circular, toothy jaws—thrived on speed and weirdness, and Dunkleosteus later took the crown with its armoured skull and bone-splitting bite, the ancient sea scorpion leaned into a balanced cocktail of agility, armour, and ambush tactics. It could swim, crawl, and possibly even clamber ashore, giving it an edge over fully aquatic creatures with limited escape options.

Compared to early jawless fish and sluggish trilobites, sea scorpions were both predators and nightmares. Their articulated pincers offered a precision that most rivals couldn’t match. Fossil evidence shows some species were capable of sophisticated hunting strategies—stalking prey in the shallows, then lashing out with a speed that belied their size. Jaekelopterus, the heavyweight of the bunch, was longer than a grown man and likely capable of taking down most things unfortunate enough to swim within reach.

But even the sea scorpion had competition. As life diversified, new threats emerged: giant amphibians, early sharks, and armoured placoderms began testing the balance of power. Yet for a good stretch of geological time, the ancient sea scorpion didn’t just survive—it thrived, adapting across millions of years and dozens of environments, while many of its rivals flickered out.

What makes this creature stand out isn’t just its size or longevity—it’s that it was among the first to master the art of predation. In a world still figuring itself out, the ancient sea scorpion had already written the rulebook. Its place in the food chain was earned, not inherited, and every claw mark in fossilised sediment tells a story of an ecosystem where survival was innovation, and dominance came with legs, paddles, and an unrelenting grip.

Dive even deeper into prehistory with our feature on giant ancient sea creatures that once dominated Earth’s oceans.

The Legacy of the Sea Scorpion in Myth and Culture

Though long extinct, the ancient sea scorpion may have left more than just its fossilised armour behind—it may have slipped into the fabric of our collective imagination, surfacing in myth, legend, and the haunting tales that echo through maritime folklore. There’s something undeniably primal about a creature that looks like a weapon crafted by the sea itself. When early humans stumbled across its remains—clawed, ridged, and imprinted into stone like nature’s own hieroglyph—they didn’t see science. They saw monsters.

Before palaeontology gave these creatures names like Eurypterus or Pterygotus, it’s not hard to imagine sailors and villagers turning their fossilised remains into stories. Giant claws embedded in cliffs. Armoured plates pulled from the earth. Whispered tales of sea beasts that once crawled ashore under cover of darkness. In coastal communities from Scotland to Estonia, where many of the largest sea scorpion fossils have been found, local legends often spoke of sea monsters that stalked the shallows or vanished warriors turned to stone. It’s tempting to wonder whether these stories were inspired—at least in part—by the silent fossils underfoot.

In the ancient world, the sea has always been a place of transformation, of danger and mystery. Cultures from the Greeks to the Norse filled the oceans with creatures symbolic of fear, chaos, or divine power. While there’s no direct evidence that the prehistoric sea scorpion inspired specific myths like the kraken or sea serpents, their monstrous appearance and scale certainly fit the bill. Their armoured exoskeletons and predatory claws may have fed the archetype of the “clawed sea beast”—a recurring motif across maritime legends and artistic depictions.

Even today, sea scorpions capture the creative eye. Artists and storytellers continue to draw on their eerie forms to imagine otherworldly creatures for film, literature, and games—ancient monsters resurrected in pixels and ink. Their legacy survives not just in museums or stone slabs but in the myth-making instinct that still lingers in us: the need to name the unknown, to make sense of what we fear, and to keep telling stories about what might still be lurking beneath the waves.

If the sea’s ancient secrets fascinate you, explore the legend of the lost underwater Mayan city hidden beneath the waves.

What Ancient Sea Scorpions Teach Us About Evolution

The story of the ancient sea scorpion isn’t just a tale of monstrous size or mythic intrigue—it’s a fossilised lesson in how life adapts, transforms, and sometimes disappears entirely. As one of the earliest known apex predators, the sea scorpion carved out its ecological niche long before complex vertebrates entered the scene. Its existence gives us a rare window into the evolutionary experiments of early marine life and the origins of movement, dominance, and survival in aquatic ecosystems.

What makes Eurypterids so valuable to evolutionary science is their position on the timeline. These creatures bridge the gap between simple, soft-bodied lifeforms and the more complex arthropods and vertebrates that followed. Their jointed limbs, compound eyes, and armoured exoskeletons speak to a sophisticated body plan that allowed them to thrive in an ever-changing world. They weren’t mindless bottom-dwellers—they were mobile, reactive, and in some cases, adaptable enough to venture onto land. That amphibious ability hints at one of evolution’s greatest transitions: the shift from water to land.

Some fossil evidence even suggests ancient sea scorpions may have moulted on shorelines, much like modern-day crabs and horseshoe crabs. These behaviours, if confirmed, put them among the earliest animals to interact meaningfully with terrestrial environments—a bold move in evolutionary terms. It’s here, at the muddy fringes of ancient coastlines, that we begin to see the seeds of future land-dwelling arthropods, and eventually, the ancestors of spiders, insects, and scorpions themselves.

They also challenge our assumptions about what evolution “should” look like. For hundreds of millions of years, sea scorpions were dominant, well-adapted, and widespread—and yet, they’re gone. Their extinction reminds us that success in one era offers no guarantees in the next. Climate shifts, rising competition, and changing oxygen levels may have all contributed to their downfall, making them a powerful case study in extinction as much as adaptation.

Even in death, they serve a purpose. By examining the evolutionary innovations of ancient sea scorpions—swimming paddles, specialised pincers, toughened exoskeletons—we can trace how certain traits were refined, repurposed, or left behind in the evolutionary arms race. They were among nature’s first to truly master movement, defence, and predation in a complex ecosystem. In many ways, they wrote the manual on being a predator—long before jaws, claws, or bones came to claim the throne.

Why Did the Ancient Sea Scorpion Go Extinct?

For a creature that once ruled prehistoric seas with armoured confidence and clawed precision, the disappearance of the ancient sea scorpion feels almost poetic. After more than 200 million years of dominance, the once-mighty Eurypterids vanished from the fossil record, leaving behind only impressions in stone and whispers of their evolutionary legacy. So, what caused one of Earth’s earliest apex predators to fall silent?

Like many extinctions in Earth’s long history, the fall of the sea scorpion wasn’t the result of a single cataclysm—it was death by degrees. One major suspect is the end-Permian mass extinction—a global event around 252 million years ago that wiped out over 90% of marine species. Triggered by massive volcanic activity, this extinction led to rising temperatures, acidified oceans, and plummeting oxygen levels—conditions no marine predator, no matter how ancient or adaptable, could easily survive.

Even before this global collapse, the ancient sea scorpion was already under pressure. As life diversified, new and more efficient predators emerged. Early sharks, amphibians, and jawed fish brought with them faster swimming styles, better sensory systems, and more aggressive hunting techniques. The sea scorpion’s tried-and-true anatomy—formidable in earlier ecosystems—was slowly becoming outpaced. Nature was changing the rules, and Eurypterids were finding fewer places to hide, fewer prey to stalk, and more threats at every turn.

There’s also evidence that environmental shifts played a slower, more insidious role. Changes in sea levels and coastal geography may have reduced the brackish and shallow habitats that sea scorpions depended on. As their ecological niche shrank, so too did their populations. Fossil records show a steady decline in diversity leading up to the Permian, hinting at a species struggling to keep pace with a world moving on.

But perhaps what’s most compelling about their extinction is what it reveals about resilience and fragility. The ancient sea scorpion, once a master of the oceans, was not immune to time’s tide. Its extinction is a stark reminder that even the most dominant species can fade when adaptation stalls and conditions shift just enough to tip the balance.

Where to See Ancient Sea Scorpion Fossils Today

There’s something profoundly humbling about standing face to face with the fossil of an ancient sea scorpion—a creature that once ruled the oceans when land was barren and the sky unfamiliar. These relics are more than stone impressions; they’re echoes of a lost world, locked in sediment and time. And for those intrigued enough to follow their clawed trail, there are a handful of places around the world where you can see these prehistoric predators up close.

In Scotland, the Pentland Hills near Edinburgh hold some of the most significant sea scorpion fossil discoveries. The region’s Silurian-aged rock layers have yielded beautifully preserved Eurypterid specimens, capturing fine details like paddle limbs and segmented tails. Some of these are now housed in the collections of the National Museum of Scotland, where visitors can get a close look at creatures that once prowled the very ground beneath their feet—albeit underwater.

Across the Atlantic, New York State offers another window into this ancient world. The New York State Museum in Albany showcases fossils from the renowned Herkimer and Otisville formations, where fossil hunters have uncovered multiple species of sea scorpions embedded in Devonian-era shale. These fossil beds are part of what was once a vast inland sea, and they remain a magnet for amateur palaeontologists and researchers alike.

For those travelling through Europe, Germany and Estonia also boast remarkable fossil finds. Museums like the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt and the Estonian Museum of Natural History in Tallinn hold stunning examples of ancient sea scorpions from local sites, offering a glimpse into what swam through their prehistoric landscapes. Some of the largest and most complete specimens, including the infamous Jaekelopterus rhenaniae, have been discovered in the German Rhineland.

In the UK, you’ll also find Eurypterid fossils on display at the Natural History Museum in London, a must-visit for fossil lovers. Their collection includes specimens from British sites and beyond, often accompanied by reconstructions and illustrations that help bring these long-extinct predators back to life.

Whether it’s through museum glass or on a windswept fossil-hunting trail, witnessing the remains of an ancient sea scorpion is a powerful reminder of Earth’s deep-time mysteries—and the strange, silent creatures that came long before us.

For a deeper dive into the fossil evidence and scientific classification of these ancient arthropods, visit the Smithsonian’s overview on ancient sea scorpions.

Real-World Questions About Ancient Sea Scorpions (SEO-Driven Q&A Section)

Curiosity about the ancient sea scorpion goes far beyond academic circles. From fossil fans to folklore followers, people still ask questions that reach into both science and imagination. These are the real-world queries echoing across search engines, museum halls, and Reddit threads—rooted in wonder, and backed by our ongoing obsession with what once ruled the ancient seas.

Are ancient sea scorpions still alive today?

No—Eurypterids went extinct around 250 million years ago during the Permian mass extinction. While their modern arthropod relatives, like scorpions and horseshoe crabs, still roam land and sea, the ancient sea scorpion is well and truly a relic of the past. Any whispers of survival are best left to sea monster legends and cryptid lore.

What is the largest ancient sea scorpion ever discovered?

That title goes to Jaekelopterus rhenaniae, a true leviathan of the arthropod world. It’s estimated to have reached 2.5 metres in length—about the size of a small car—making it one of the largest known arthropods in Earth’s history. Fossils from Germany’s Rhineland preserve parts of this beast’s claws, offering tangible proof of its terrifying scale.

Could ancient sea scorpions walk on land?

Possibly. While they were primarily aquatic, some species show adaptations that hint at short stints on land—likely during moulting, mating, or escaping predators. Their closest living relatives, horseshoe crabs, already do this today. So while they weren’t strolling through forests, brief shoreline adventures may have been part of their lifecycle.

⚔️ How did ancient sea scorpions hunt?

They were ambush predators, using large pincers to seize soft-bodied prey like early fish or other invertebrates. With their compound eyes and paddle-like limbs, they could glide through shallow waters and strike with speed and precision. Some may have buried themselves in sediment, lying in wait like scaly trapdoor hunters.

Did ancient sea scorpions have venom or stingers?

Unlike modern scorpions, there’s no direct evidence that ancient sea scorpions possessed venomous stingers. Some had spiked tails, but these were likely used for balance or swimming rather than injection. Their real threat came from their sheer size and crushing pincers—not chemical warfare.

What animals are related to ancient sea scorpions today?

Despite the name, sea scorpions are more closely related to horseshoe crabs and arachnids than to modern marine scorpions. They’re part of the arthropod lineage—one of the oldest and most diverse branches in the animal kingdom. Their descendants include spiders, ticks, and mites, though none quite capture their aquatic menace.

Where have ancient sea scorpion fossils been found?

Fossils have turned up across Europe and North America, particularly in Scotland, Germany, Estonia, New York, and Ontario. These ancient sedimentary layers were once seabeds and estuaries—perfect places for sea scorpions to live, die, and fossilise into the legends they are today.

Every question about ancient sea scorpions is really a question about our own curiosity—our urge to understand what came before us, what shapes life has taken, and what stories still rest in the stones beneath our feet.

Final Splash: What Ancient Sea Scorpions Remind Us About Earth’s Depths

The ancient sea scorpion may be long gone, its last paddle stroke lost to prehistoric tides, but its story still ripples through time—etched into stone, lore, and our collective fascination with the unknown. More than just a fossilised predator, the sea scorpion is a reminder that Earth’s greatest dramas have often unfolded beneath the surface, in waters that once teemed with creatures stranger than anything our imaginations could conjure.

It teaches us that dominance is never permanent. Even the most finely tuned predators—adapted, agile, and armoured—can be undone by a planet that never stops shifting. The sea scorpion’s tale speaks to the fluid nature of evolution, where extinction is just another part of the narrative, and survival favours the nimble, the niche, the new.

But beyond the science, there’s something poetic in knowing that such creatures once existed. They invite us to look at the ocean not just as a body of water, but as a living archive—an ever-moving mirror that reflects where life began, what it’s capable of becoming, and what it’s already lost. In the ancient sea scorpion, we glimpse the beginning of the predator’s path, the roots of biological innovation, and the echo of a world that breathed in silence and shadows, long before we ever arrived to give it a name.